A second patient with HIV has been cured In 2008, the “Berlin patient” became the first person in the world to be cured of HIV thanks to a stem cell transplant at the Charité – Medical University of Berlin. In both cases, the patients received treatment for blood cancers using stem cell transplants and the donors were specially selected by researchers. HIV is a generally incurable disease. After the transplant, the current patient has had no detectable virus for more than five years, even though he is not taking antiviral drugs.

The first patient in Berlin received stem cells from a donor who was homozygous for CCR5, a gene that can protect against HIV infection but is very rare. The donor of this second patient was heterozygous for CCR5. Why this patient was cured while the virus has replicated again in comparable cases remains unclear. Researchers are considering multiple potential factors.

This new case will be presented at the International AIDS Conference in Munich on July 24.

In 2008, a team at Charité demonstrated that stem cell transplants work against both HIV and cancer when they were administered to a person known as the “Berlin patient.” Since then, four other people around the world have received the treatment and are now considered to have been cured of HIV.

Stem cell transplants are only used in patients who have HIV and develop certain forms of leukemia or lymphoma that do not respond to radiation or chemotherapy. In this type of transplant, stem cells from a healthy person are transferred to the patient to basically replace his or her immune system. If engineered correctly, these cells can fight both cancer and HIV.

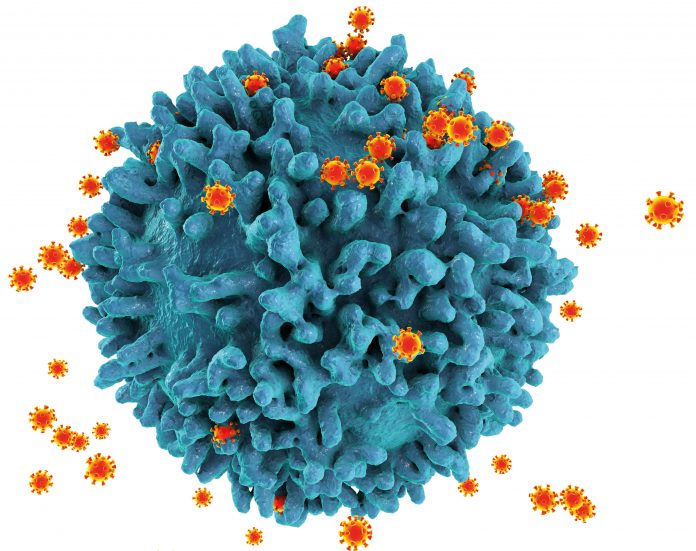

In order to multiply, HIV needs the CCR5 receptor to enter immune cells. Only about one percent of the European population has a CCR5 receptor with what is known as the delta 32 mutation. It prevents the virus from entering, making people with this mutation naturally immune to HIV. If it is possible to find a stem cell donor whose tissue is compatible with the recipient, and If that person is a carrier of this immunity-causing mutation, then stem cell transplantation can cure not only the patient’s cancer, but also HIV.

The second patient, now 60, tested positive for HIV in 2009 and was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukaemia in 2015. He was treated as a leukaemia patient by a team from Charité’s haematology, oncology and cancer immunology department. The patient’s risk profile made it necessary for him to undergo chemotherapy and an additional stem cell transplant.

“We were unable to find a compatible stem cell donor who was immune to HIV, but we did manage to find one whose cells have two versions of the CCR5 receptor: the normal one and a mutated one,” explains Dr. Olaf Penack, MD, PhD, head of the department treating the patient. “This occurs when a person inherits the delta 32 mutation from only one parent. However, having both versions of the receptor does not confer immunity to HIV.”

Although the donor was not immune, it became clear that the stem cell transplant had successfully cured HIV after the patient independently stopped the recommended antiviral treatment in 2018.